- Home

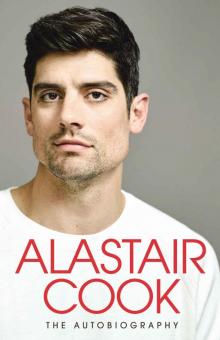

- Alastair Cook

The Autobiography

The Autobiography Read online

Alastair Cook

* * *

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

with Michael Calvin

Contents

Picture Credits

1 Digging to the Well

2 Boy to Man

3 The Survival Gene

4 Collateral Damage

5 The Zen of Opening the Batting

6 In the Bush

7 Honesty

8 Baggy Green

9 View from the Mountain Top

10 Decline and Fall …

11 Fallout

12 Redemption

13 Sanctuary

14 Spirit of Cricket

15 Passing the Torch

16 Names and Numbers

17 Not Found Wanting

Epilogue: One Moment in Time

Illustrations

Appendix: A Career in Numbers

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

Alastair Nathan Cook was born in Gloucester, December 1984. He is an English cricketer. He plays for Essex County Cricket Club and previously for England. Cook is the fifth highest Test scorer of all time.

He is regarded as England’s most successful batsman ever and now he is an icon and role model in sport.

Outside of cricket, Alastair has written columns in the Telegraph and Metro, he is a talented saxophone player and donates his time to raising money for cancer charities and the David Randall Foundation. He is now married with three children.

For Elsie, Isobel and Jack

Picture Credits

Pictures 12, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25 courtesy of Alastair Cook

1. © Adam Davy/PA Archive/PA Images

2. © Adam Davy/PA Archive/PA Images

3. © Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

4. © Hamish Blair/Getty Images

5. © Jordan Mansfield/Getty Images

6. © Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images

7. © Scott Heavey/Getty Images

8. © Mike Egerton/EMPICS Sport/PA

9. © ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images

10. © Gareth Copley/Getty Images

11. © Tom Shaw/Getty Images

13. © Popperfoto/Getty Images

14. © Gareth Copley/Getty Images

15. © Gareth Copley/Getty Images

16. © Michael Steele/Getty Images

17. © Michael Dodge/Getty Images

18. © Gareth Copley/Getty Images

19. © Gareth Fuller/PA Wire/PA Images

21. © Dominic Lipinski/PA Wire/PA Images

1. Digging to the Well

‘I’m sorry, lads. I can’t believe I just got out like that.’

Joe Root, waiting on the glass-fronted balcony of the dressing room at the Oval, smiled, slapped me lightly on the back and told me to ‘shut up’. He probably had a point, since the old ground hummed with excitement and commentators were suggesting I was some sort of national treasure, but batting is a serious business.

Joe followed me through a second doorway into an inner changing area, where I took twelve paces to my double peg close to the far right-hand corner. Life went on; the rhythm of professional sport is set by personal priorities, and Jos Buttler, surprised by the sudden fall of wickets, bustled in to complete his preparatory rituals.

After a brief flurry of congratulation, I was left to myself. I sat there for three or four minutes with my pads still on, savouring the silence and sifting through my senses. I looked around, through the organized chaos of discarded kit, lotions and potions. I was in a special, sacred place, where harsh truths are occasionally shared, yet balanced by the intimacy of individuals involved in something bigger than themselves.

The dressing room is a sanctuary, safe from the second guessing of social media and the exaggerated attention of the outside world. It is unique, precious. Each team is different, a collection of distinctive personalities, but this is the only place in which it can truly be itself. I loved that feeling of solidarity, freedom and friendship; that’s why, as captain, I encouraged players to linger over a beer at the end of play.

Disappointment, even one as strictly relative as being dismissed carelessly for 147 in my final Test innings, has certain formalities. I’ve never been a bat-thrower, a blame-shifter or excuse-seeker. I prefer quick and quiet rationalization; my instinctive apology might have been a bit cloth-eared, but losing two wickets, especially those of well-set batsmen, to successive deliveries is a cardinal sin.

In time, it will be a killer pub-quiz question: name the Indian Test debutant who dismissed two England captains in two balls. Hanuma Vihari is an occasional right-handed off-spinner, a dispenser of what old pros refer to as ‘filth’. There’s no disrespect implied, intended or taken in that, by the way. It is merely our form of industrial language.

Rooty had holed out to midwicket for 125. In a world of fine margins, my mind wasn’t locked in to the next ball. It was dragged down and I got a little greedy. Instead of making the slightly easier shot, in front of square, I acted on the momentary mental image of a thin gap between two fielders behind the wicket.

I wasn’t consciously thinking of the boundary that would have taken me past 150, but I lacked that critical edge of concentration. I smiled and sagged forward, leaning on my bat momentarily, because I couldn’t believe I had edged it to the wicketkeeper. All that was left was that final walk to the pavilion, bat aloft and brain whirring.

I noticed the dressing-room TV was replaying those scenes as I sat there, decompressing. The screen showed Alice, my wife, cradling our daughter Elsie and telling her ‘there’s Daddy’. I didn’t cry, despite the temptation; the closest I came to doing so was during that amazing extended ovation for my second-innings century. There wasn’t an ounce of me that wanted to carry on. I was done.

The only time in my career I wept uncontrollably was in the dressing room at the MCG during the Boxing Day Ashes Test in 2017. I was 104 not out at the close of play on the second day, on my way to carrying my bat for 244, and couldn’t stop myself. I was as puzzled as anyone; on reflection, it was a moment of release after sustained private questioning of my mood and motives.

Retirement is not a snap decision, because representing your country is the greatest of an athlete’s privileges. It rattles around the brain for months, sometimes years, and ambushes you when you least expect it to. For me the process began at Edgbaston in August 2017, during the first Test against the West Indies, when Rooty joined me at the crease. We were 39–2 and facing an all too familiar obligation to build a score.

I might have looked calm and dispassionate to the casual spectator, but I felt an enormous weight of expectation, an insidious surge of pressure. That inner voice, a cold, caustic commentator on my faults and weaknesses, piled in on cue: ‘Here we go again,’ it said. ‘Why are you putting yourself through this mental torture? You’ve got nothing else to prove.’

I went on to score 243. Joe made 136 and we won by an innings inside three days. But a pebble had been dislodged; an internal conversation with an inevitable conclusion was underway. This wasn’t about anything as selfish as personal achievement; it was a private progression of truth and reconciliation. I had to be true to myself, and my teammates.

A player dealing with personal turmoil needs a coach who empathizes with his dilemma. Mark Ramprakash, England’s batting coach, was the first person I turned to, as we walked back from a net session before our second warm-up match of that winter’s Ashes tour, a day–nighter against a Cricket Australia XI at the Adelaide Oval.

Ramps was, by common consent, the most technically accomplished batsman of his generation. He was a driven character, an accumulator of 114 centuries, who retired with a first-class average of 53.14 a couple of months before his forty-third b

irthday. He fought against the dying of the light but understood where I was coming from.

‘I don’t know why I’m doing this any more,’ I confessed. ‘How many times do I have to dig to the well before there is nothing left?’ That’s a horrible phrase, a reflection of declining hope and increasing desperation. I was only thirty-two, theoretically years away from unarrestable decline, yet mental decay had set in.

Physically, I was fine, the fittest I had ever been. The ECB had looked after me exceptionally well, streamlining my schedule so that I had the occasional respite of a couple of months at home. A governing body of any sport has a corporate dimension, but behind the scenes it has good people on whom we rely as players.

Our families are hugely grateful to Medha Laud, whose liaison work has taken cricket out of the Dark Ages, the pre-Duncan Fletcher era in which tours were planned without thought for a player’s personal life. This inevitably added to the strain on relationships, and caused quiet resentment. Medha is thoughtful, efficient and empathetic; her MBE for services to cricket was widely celebrated.

Another long-term member of the support team, Phil Neale, makes sure everything runs smoothly. He has been the England team’s operations manager since 1999, and utilizes a huge range of experience, as the last of the old-time footballer-cricketers. He played 358 matches for Lincoln City and 354 first-class games for Worcestershire, where he was captain for ten years before moving into coaching. He is as likely to be found helping slip practice as organizing our bags.

The old grind of airport–hotel–ground–hotel–airport had been minimized by modern performance planning, but eventually in a sport like ours, resilience wears thin. I was going through the motions of stretching, lying on the outfield in Christchurch midway through the second Test during the subsequent series in New Zealand in March 2018 when I unburdened myself to Chris Silverwood, England’s bowling coach. We were at ease in each other’s company, having just shared Essex’s title win in the County Championship.

I had scored twenty-three runs in my four Test innings in a losing series and was thinking beyond a match we were destined to draw. ‘I’m done with it,’ I told him. He didn’t seem desperately surprised, but urged caution: ‘Look, whatever you do don’t say anything. Obviously, you’ve had a tough tour and a tough winter. Just get through the next two days, then go home and see how you feel.’

I had begun to dread net sessions. I had always found them hard work throughout my England career and disliked their imperfections. Everyone oversteps the mark, bowling from seventeen or eighteen yards, no matter how stringent the bowling coach. They’d argue it was irrelevant, since they didn’t bowl no-balls when it mattered, but it was a constant source of irritation.

There is a time for experimentation in the nets, but I hated the embarrassment of getting out. I never wanted to give my wicket away, whatever the circumstances. When I allowed myself to be more proactive, I would try new things away from prying eyes, in a private session with our batting coach, Graham Gooch. Seeing people showboat, trying to sweep flashily or hit every ball over the top, used to get to me.

Nets can be subtly confrontational. I can’t lie – I used to love it when I got Jimmy Anderson or Stuart Broad. I knew Jimmy would be bowling at 75 per cent, which is bloody hard work but manageable, and Broady wouldn’t be trying to prove himself too often. Emerging bowlers such as Chris Woakes or Mark Wood would seek to make a personal statement in every session.

As captain, I understood and applauded that, but as a batsman, seeking rhythm in England in early summer, where nets are not as flat as they are on the subcontinent, the challenge became claustrophobic. I’d maintain my performance level, operating at about 98 per cent of my capacity over three twenty-minute sessions, often against lads I’d never seen before, but it became wearing.

I consulted with Mark Bawden, England’s team psychologist, about how I could deal better with the dilemma. We spoke about having a very clear focus, a specific task to work through before a particular match, but eventually the dials just went round and round without registering. I made a conscious effort to sustain my intensity, but it became more of a chore.

Once instinct tells you the end is near, lethargy seeps into the system like slurry in a watercourse. Most people can’t detect the difference, but long-term teammates have a sixth sense for mood swings. I’d played with Broady for eleven years; one throwaway line after a net session early in that final series against India told me he knew, deep down, what I was fighting.

‘Jeez, you’ve finished already?’ he said with arched eyebrows. I’d just done an hour’s batting and catching, but he’d seen something. I might not have hit as many balls as usual; I could have been unconsciously hasty in heading back to the pavilion. Whatever it was, he hit the mark, because, as he told me when I eventually confirmed my retirement, ‘We’re pretty similar, aren’t we?’

Game recognizes game at the highest levels of international sport. Jimmy had just bowled at 75 per cent for an hour. He never missed a length, and it looked as if it had taken nothing out of him. I knew that his ankle, shoulder and elbow hurt, but it looked so easy. Broady, standing beside me, murmured, ‘If I did that, I’d be all over the place.’

He had to charge in, in every net session, to reach the standards he expected of himself. He knew that if he tried to be self-contained, in Jimmy’s fashion, he would bowl poorly, and be difficult to deal with while he worked through the frustration. I can say that as a friend, because we have so much in common. We’ve made the most of any ability we’ve been given, but it has taken a lot of effort to do so.

I’d lost that edge. I played out certain scenarios in my mind – obviously finishing with a home Ashes series in 2019 would have been ideal – but getting out for 13 and 0, to a couple of good deliveries, in the first Test against India at Edgbaston that summer of 2018 proved to be a persuasive reality check. My mind was finally made up during the third Test at Trent Bridge.

This wasn’t submission to the self-doubt that inevitably creeps in during a run of low scores; it was the liberation of sudden clarity that there was only one solution to the problem. I arrived back at the team hotel on the third evening of the match, when I was 9 not out overnight, fully intending to tell Alice I was in my last series. She was heavily pregnant with our son Jack, and to wind down, with the girls asleep next door, we watched the Inbetweeners movie in bed.

I fall asleep to the TV series on tour all the time. It has a comforting familiarity; I know all the words, and I’m usually out like a light before the introductory music ends. I’ve only watched the movie occasionally; that night we laughed out loud at the adolescent antics. I knew I had to tell her, but it seemed wrong to darken the mood.

Instead, I ignored the ICC anti-corruption code (belated apologies, chaps) and didn’t hand my phone in when I reported to the ground the next morning. I texted Alice: ‘Are you OK? I’ve got to tell you this. The end of this series is going to be my last game for England.’ I saw the two blue ticks on WhatsApp, which signalled that she had read it, and felt a sudden nervousness as the word ‘typing’ appeared on screen.

I was thinking, ‘Please don’t fight it,’ and praying for her acceptance. She had been a constant source of strength when I’d struggled with the complexities of captaincy, and the isolation of life on a difficult tour. We’d had a couple of long telephone conversations from Australia that winter, and she was attuned to my tentative cries for help. It seemed to take for ever for her to reply, but when she did so, she needed only two words.

‘I know …’

Relief accompanied the realization that my inner struggle must have been blatantly obvious. Alice is, after all, the person who knows me better than anyone. I found a quiet anteroom in the changing area and made a call: ‘I just can’t keep going,’ I told her. ‘I’ve lost what makes me different from everyone else and I want to go out with my head held high.’

Weight lifted, I ran rapidly through my priorities. I told Jimmy first, a

s we sat on the balcony watching the day’s play. I had my sunglasses on as usual, pulled my cap down low and indulged my habit of chewing the collar of my sweatshirt. ‘I’m really sorry I’m doing this to you now,’ I said, behind a casually cupped hand, ‘but I’m packing it in.’ His face was a picture. ‘I can’t believe it,’ he said. ‘Are you sure? I’m sad – sad but shocked.’

Rooty was next on the list. I arranged to play nine holes with him on the golf course adjoining the Ageas Bowl in Southampton, before training began in earnest on the following Tuesday. I suspected, correctly, he had sussed out what was going on, but wanted to tell him face to face. I told Broady on the outfield the next morning; the secret was safe with all three.

Was there any need for the cloak-and-dagger stuff? Probably not, though I didn’t want to be a distraction. Trevor Bayliss, the England coach, told me that, for the first time, the selectors were discussing my position. ‘That’s absolutely understandable,’ I acknowledged. ‘I haven’t delivered a good stat this summer and have had a couple of big scores with not much in between for twelve months, but you don’t have to worry. The next game will be my last, if I’m picked.’

He looked at me inscrutably: ‘Oh, right. Thought that might happen …’

Trevor and Rooty led a happy dressing-room debrief immediately after we clinched the series by winning that Test, before handing over to me. I was a few beers in at that time, to quell the nerves, because I didn’t know how I was going to react to telling the rest of the lads. I didn’t go full Oscar acceptance speech, but my voice caught a couple of times.

The scene encapsulated what I will miss in the years to come. The deep satisfaction of the group, sharing the exclusivity of the moment. Job done, juices flowing, tension eased. ‘This might be a sad day for some people or a happy day for others,’ I announced, ‘but I just want to let you know that my next Test, if picked, will be my last. I’ve run out of steam and this has been a great way to finish.’

The Autobiography

The Autobiography